Loops

Definition

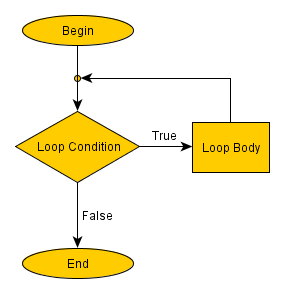

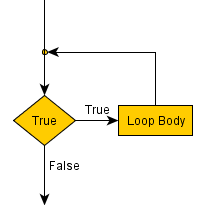

Loops are constructions, that allow us to execute one or several actions multiple times. They consists of two major parts: a truth condition and a body. The body contains the actions that we want to repeat. Each execution of the body block is called iteration. The condition decides whether the iterations will continue or not.

Usage

Imagine that you need a program that has to repeat something a million times! Would you re-write the same thing 1 000 000 times? Or you would rather use the simple construction of several blocks that do the repetition for you? Of course, the latter ;). See the example below, it is so simple, yet so powerful:

Initially the program checks the condition. Lets say that it is true and we enter the body, where our actions are executed. Following the body we cycle back and do the check again. If it is still true, then the program will make one more iteration. Once it is false, the execution continues with the block following the loop (in the example above the algorithm ends).

The body could be as complex as we need it. We may create it to be very simple (for example only one action block) or we could put a series of different blocks.

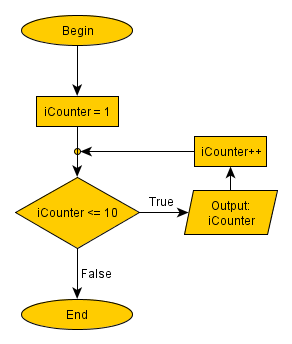

Example: Print the numbers from 1 to 10.

In this short algorithm we will repeat the output and the increment of the variable iCounter. Once iCounter is not <= 10, the program completes.

Precondition loops

Precondition means, that the check will be done before the body execution. Notice that such construction might quit before executing its body even once(zero iterations) if the condition is false the first time. The examples that we have looked at, so far are all with precondition.

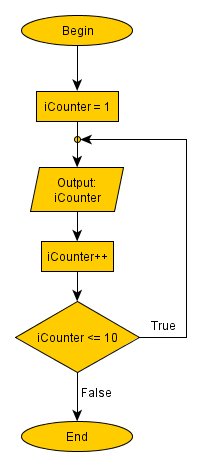

Postcondition loops

They do the end-check after their body. Because of their

structure they guarantee that the body

will execute at least once.

There is no better or worse between pre- and post-. You decide which one to use, depending on the situation. Most times it doesn't matter, except for some very rare cases.

Here is the previous example, solved using post-condition:

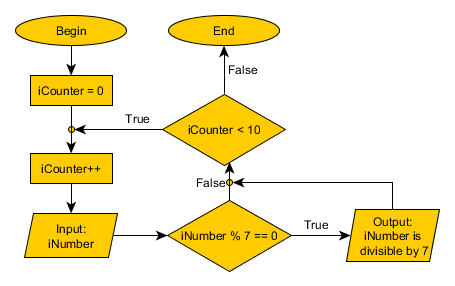

Example: Write a flow chart for an algorithm, that accepts 10 numbers from the user. Check whether each number is divisible by 7 without reminder. Use a postcondition.

Infinite loop

Normally we will continue to repeat the iterations while the condition is evaluated to true and stop when it becomes false. If this never happens it will have infinite number of iterations. Usually this happens by mistake and causes the program to crash, giving a “stack overflow” exception.

Example of such mistake is, if we miss to increment the iCounter variable in the above algorithms. In some rare cases we may want to create this kind of behavior. The easiest way to do this is to put the Boolean value true in the condition.

One way to use infinite repetitions is to quit

the loop from within its body. We will look at this in another tutorial.

Good practices

Often you will need to do a certain number of iterations. Usually we use a counter variable to count them and compare it to the final value. It is a good practice to compare it to the number of repetitions we will do, if possible.

For instance, the examples above

use the end condition iCounter < 10, because the number of iterations is

10. The same logic could be implemented with the check iCounter <= 9, but it

is not as convenient as the above.

Homework

Write a program which:

- outputs the numbers from 100 to 0 (100, 99..0).

- outputs all even numbers between 5 and 50.

- takes an input number from the user and saves it in the variable K. Then the algorithm outputs the first K numbers, divisible by 5 without reminder.

- Try to optimize the algorithm from task 3, so that the body of the loop executes K-times.

- Output the first 15 numbers from the Fibonacci sequence. The first two are 0 and 1. Each next is calculated as a sum of its two preceding numbers. The third is 0+1 = 1, the fourth is 1+1=2 and so on (0,1,1,2,3,5,8…)

|

Previous: Logical Operators |

Next: Nested Loops |

Tutorial Contents:

1)Learn

Computer Programming

2)Software Development Process

3)Flow

Chart

4)Flow

Chart Symbols

5)Data

Type

6)What is a variable

7)Math

Operators

8)Logical

Operators

9)Loops

10)Nested Loops

11)Arrays

12)Multidimensional arrays

13)Programming Questions

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!

Manage the football team of your city and make them champions!